- February 20

Republican General Asensio Torrado resigns his post as head of the Central front. Torrado is one of the few ‘Africanista’ Republicans who did not side with the Nationalists at the outbreak of war. Immediately after the initial coup, he led teams of soldiers in the Somosierra area just north of Madrid as well as the Battle of Talavera de la Reina. By October he was sub-secretary for war and leader of the Central Army by November, one of the leaders during the defense of Madrid. He created mixed brigades of men, both trained and those men new to fighting, to create stronger brigades. He was rejected by both anarchist ans communists due to his military-style control of the militias, and was forced to resign after the Republicans failure in Málaga.

February 21

The Non-Intervention Committee set up by the League of Nations officially bans all foreigners volunteering to fight in Spain, useless as thousands have now entered the country, defying their countries, or claiming statelessness. The Non-Intervention Committee is letting large countries such as England, France and the U.S sit on their hands, while individuals worldwide (even as far away as New Zealand) see the need to help Spain. German and Italy defy the ban daily by supporting Franco, and the Soviet Union aides the Republicans.

Captain Merriman prior to his injuries

Captain Merriman prior to his injuries

February 23

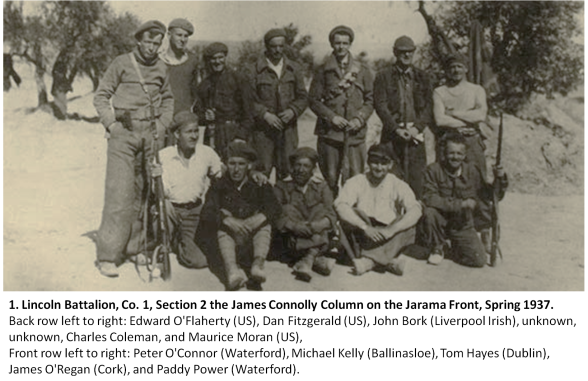

The battle of Jarama is ongoing, but with the stalemate at the front line, snipers are killing on both sides, with no progress being made. The new Abraham Lincoln battalion are ordered to take Pingarrón (Suicide Hill) again, and send 450 Americans (supported by an Irish column) off to their first major offensive, one known already as a disaster thanks to previous battles. The men have no artillery or planes for support, but storm the Nationalists over four days, and are violently killed. The battle hears the immortal words of Irish poet Charles Donnelly – ‘even the olives are bleeding’, just before he is killed by machine gun. The Americans lose 127 men and another 200 are wounded, Captain Robert Merriman included, and mutiny ensues. Other Republican units catch those who mutiny to be court-martial, but the Soviets prevent them from being tried or punished. Naturally blame needs to be passed, and XV International Brigade Commander Vladimir Copic is named, who in turn blames wounded Captain Merriman. This marks the end of the battle of Jarama, as both sides are now totally exhausted and nothing can break the stalemate. The front line shall remain here for the rest of the war, a little over two years away.

The Battle of Cape Machichaco begins. The Basque Auxiliary navy, supporting the Republican navy, send four trawlers from France to Spain – the Bizcaia, Gipuzkoa, Donostia and Nabarra. They accompany the Galdame, carrying people, machinery, weapons, mail supplies and 500 tonnes of nickel coins, all owned by the Basque government. The Nationalists send the Canarias from port in Ferrol to stop the Galdame reaching the Basque ports.

By the following morning, the Canarias was spotted by the Gipuzkoa only twenty miles from Bilbao. Shots were fired, hitting Gipuzkoa on the bridge. Returned fire kills a seaman on the Canarias, and wounds others, forcing them to retreat. The Nabarra and Donostia engage in battle with the Canarias for hours before they are forced to retreat. The Nabarra is hit at the boiler and 29 are killed, including their captain. Another twenty men are forced to abandon ship. All the men are picked up by the Nationalist Canarias and treated for their injuries.

The Galdame is also hit by the Canarias and is captured by the Nationalists, and four are killed in the carnage. Gipuzkoa manages to get to port in Portugalete and Bizcaia lands in Bermeo. Donostia lands in France. The twenty survivors of the Nabarra are sentenced to death by Franco, but the Canarias captains beg mercy, and the men are released in 1938. On board the Galdames, the passengers are let go, expect for politician Manuel Carrasco Formiguera from Catalonia, who is jailed before his execution a year later.

Trouble begins to mount as the PCE – Communist Part of Spain – holds its first council. They agree to favour democracy, against revolution and Trotskyism. The trouble is that this flies in the face of their allies, the Republican movement, the Spanish government and the powerful anarchist CNT. This decision will bring in-fighting among the Republicans in coming months, weakening the entire movement.

The Nationalists, fuelled with Spanish, Moorish and Italian soldiers, are preparing to attack Guadalajara, 60 kilometres north-east of Madrid. After all the failed attempts to take Madrid, and the collapse of battle at nearby Jarama, the Nationalists are keen to engage again. The Italians, fresh from taking Málaga, are ready to fight. The Nationalists have gathered 35,000 men, hundreds of artillery supplies over 100 tankettes, 32 armoured cars, 3,600 vehicles and 60 planes. Much of the tank, car and plane equipment comes from the Italians, as Mussolini strongly supports the offensive.

The Republicans are the 12th division of the Republican army with only 10,000 men, but only 5,900 rifles, 85 machine guns and 15 artillery pieces. They do have a few light tanks on their side. Guadalajara, until now has been peaceful, so no trenches, road blocks or defensive have been set up, but the Republicans know (assume), a Nationalist attack from the south is imminent. Meanwhile, the Nationalists are preparing to attack the 25 kilometre stretch of the Guadalajara-Alcalá de Henares road, south of Guadalajara, which will cut off the main road, and five other roads which stem from the area. The enormous offensive is planned for March 8.

~~

This is not a detailed analysis, just a highlight (lowlight?) of the week’s events. Things get lost in translation – Feel free to suggest an addition/clarification/correction below. The more the world remembers, the better. All photos and captions are auto-linked to source for credit, and to provide further information.