The letters of the 1530s show a true friendship between Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer. Even as early as 1528, Cromwell was promoting Cranmer, a priest and diplomat at Cambridge, who had spent years in Spain as England’s ambassador, but who had also gained huge knowledge and understanding of reform coming out of Germany and Switzerland. Cranmer was one of the men who first looked into annulment for Henry VIII, and Cromwell found his legal arguments aligned well with Cranmer’s theological arguments. Around the same that Cromwell was brought into court by King Henry, Cranmer was a favourite of the Boleyn family. But when the annulment could not be secured in England, Cromwell set to work to dismantle the Catholic Church’s power in England, while Cranmer set off for Germany and Switzerland, to find theological supporters for Henry’s desire to remarry. On the journey, Cranmer made the decision to marry Margarete, niece to Andreas Osiander, a Lutheran in Nuremberg. Cranmer had been tragically widowed before he took holy orders,[1] but married again, firm his belief that King Henry would allow the Reformation (and its lack of clerical celibacy) to flourish in England. Precious few knew of the life of Cranmer and Margarete, Cromwell among them (who received letters talking of Cranmer’s heartbreak at having to exile Margaret and their daughter Anne in 1539).[2] Cranmer was ushered home in 1532 to take up the position of Archbishop of Canterbury, firmly supported by both Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn, who both believed he could annul the king’s marriage in that position, supported by Cromwell’s legal changes.

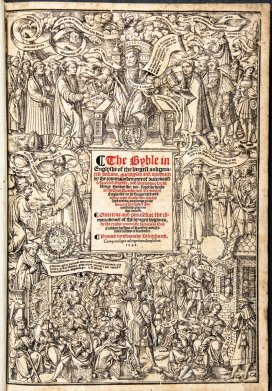

The friendship of Cromwell and Cranmer remained firm throughout the 1530s, letters frequently going between them on both serious and trivial matters, with social events shared, court events attended together, on the Privy Council and in parliament together, trusted reforms written together, and even heated arguments on many matters,[3] which never shook their friendship, as they deeply respected each other. Their work together culminated in the 1537 English bible being published, and the 1539 English Bible, nicknamed the Cranmer or Cromwell Bible, showing the two of them together, each assisting the king, and sharing the reformed word of God to the people. The 1541 edition showed a blank space where Cromwell’s banner had been, a stranger in his place assisting Cranmer, the hole on the otherwise richly decorated bible cover evident for all to see.

Thomas Cranmer was one of Cromwell’s strongest friends and allies on the Privy Council the day Cromwell was rudely arrested, and Cranmer was the only man in a politically safe position to argue Cromwell’s cause. But even Cranmer could not speak in Cromwell’s defence at his physical arrest, yet he was the man with enough courage to write to the king the very day after Cromwell went to the Tower. Cromwell’s family, friends and allies (of which there were countless) stayed silent throughout his arrest, carrying on faithfully with the positions he had given them, to ensure the wheels of England and Ireland continued turning, as he would have instructed them. Speaking up would not help Cromwell, nor the person who spoke, but Cranmer couldn’t hold back, just as he couldn’t when Anne Boleyn got arrested.[4]

Cranmer sent a letter across the Thames from Lambeth to the king, which sadly has not survived, and only a partial fragment remains. But this partial letter shows a heartbreaking plea from a man who sounds helpless over the loss of his friend and ally. The letter was printed originally in Edward Herbert, Baron of Cherbury’s The Life and Raigne of King Henry VIII in 1649, but how Herbert got hold of a copy of the letter written by Cranmer is unknown. Herbert was a colourful court character, from one of the branches of the Earl of Pembroke family tree. The Herberts were connected with the Parr and Dudley families before and after the execution of Cranmer in 1556, so it is possible the fragment was handed down that way. However, it’s impossible to know where Lord Herbert found this record, or what happened to the fragment after its original publication. The letter is also listed in White Kennett’s History of England Volume II 1706, Gilbert Burnet’s History of Reformation Vol. I 1829, John Cox’s Cranmer’s Works 1846, and John Strype’s Ecclesiastical Memorials Volume I 1882, all copied from Herbert’s writings, and not an original document. It is also sometimes dated as 14 June, but is now catalogued as 11 June, 1540.

“I heard yesterday in your Grace’s Council, that he (Crumwell) is a traitor, yet who cannot be sorrowful and amazed that he should be a traitor against your Majesty, he that was so advanced by your Majesty; he whose surety was only by your Majesty; he who loved your Majesty, as I ever thought, no less than God; he who studied always to set forwards whatsoever was your Majesty’s will and pleasure; he that cared for no man’s displeasure to serve your Majesty; he that was such a servant in my judgment, in wisdom, diligence, faithfulness, and experience, as no prince in this realm ever had; he that was so vigilant to preserve your Majesty from all treasons, that few could be so secretly conceived, but he detected the same in the beginning? If the noble princes of memory, King John, Henry the Second, and Richard II had had such a counsellor about them, I suppose that they should never have been so traitorously abandoned, and overthrown as those good princes were: I loved him as my friend, for so I took him to be; but I chiefly loved him for the love which I thought I saw him bear ever towards your Grace, singularly above all other. But now, if he be a traitor, I am sorry that ever I loved him or trusted him, and I am very glad that his treason is discovered in time; but yet again I am very sorrowful; for who shall your Grace trust hereafter, if you might not trust him? Alas! I bewail and lament your Grace’s chance herein, I wot not whom your Grace may trust. But I pray God continually night and day, to send such a counsellor in his place whom your Grace may trust, and who for all his qualities can and will serve your Grace like to him, and that will have so much solicitude and care to preserve your Grace from all dangers as I ever thought he had…[5]

~~~

Tomorrow – Ralph Sadler delivers Cromwell’s letter to the king…

~~~

[1] Parker, De Antiquiate, p. 387

[2] SP I/152 f. 118, July 1539

[3] Cranmer’s Letters, 311, 12 Oct 1535

[4] Otho, C. x. 226. B. M. Burnet, i. 320, 3 May 1536

[5] Strype’s Eccl. Mem. Vol. I. 1882, p. 561. Burnet’s History of Reformation, Vol. I, 1829, p. 569. Cranmer’s Works, 1846, p.401, Herbert, Life of Henry VIII, 1649, Kennett, History of England Vol. II., 1706.