To read part one, click here – PART 1: VENGEANCE IN THE VALENCIAN WATER Q+A

Here we go, part two of the Q+A, time for some of the more specific questions –

6 ) Did you base the characters on real-life people, like with Blood in the Valencian Soil?

Rather than look at the situations of specific individuals and make a fictional tale based on their lives, this book takes a different vein. This book follows real events (like BITVS) but has all fictional characters. This book is a snapshot of Valencia in 1957 and the characters live in what was reality at the time. I spent countless hours studying photographs and recollections of the city and its way of life at the time. I also studied the 1957 flood over the period of about a year, so I knew all the details I needed. I got to point where I knew the water level of individual streets around the city. I also walked those streets in Valencia, to visualise the scenarios for myself. All of the characters are entirely fictional, and would not want to meet these people in person!

As for the 2010 characters, they are all also fictional, but live in Spain as it was that year. One chapter sees Luna caught up in a protests in Madrid, and I made sure there was a protest in Puerta del Sol in that month, and checked what they protested against and what their signs said. The timeline is accurate, but no one is based on a real person.

Graham Hunt was kind enough to capture this, so it had to go in the book

7 ) What did you research for the book? You talk about research a lot of twitter.

Jaja, my twitter rambling coming back to bite me. Following on my from the last question – I researched a lot. For me, when I sit down to write, I need to be able to envisage the whole scene in my mind before a word can be written. When it’s based in Valencia, imagining somewhere is a piece of cake. But still, I need to know the details are in place before I can start. For example, when writing José in 1957, I needed to know what his Guardia Civil uniform looked like, or what the fashion of the time looked like in Valencia. That meant tracking down photographs in 1957. There is one scene were José has to wear what I imagine as the most ugly brown suit ever, but then in another, the smoothest grey suit you can imagine. I know both of these were on sale because I checked. I don’t spend a great deal of time on clothing unless it’s relevant to the scene, so you don’t feel bombarded with inane tidbits. But when they buy 1957 swimsuits, I checked to see what you could get at Malvarrosa at the time. Beach umbrellas are the right colour, restaurant decor is correct, street names are correct, even the flowers bought at the market are the right type. When Franco arrives, his car is the right kind, the positions are correct, the aides are dressed properly. When it comes to bullfighting, the clothes are correct, the details of a fight are correct, the feeling from the crowd is correct ( I know this because I sat there to get it right). Valencia is the perfect place to use as a location because there is just so much to see, and how much the city has changed is incredible. I have studied the detail of the city from the mid-1800’s until now and the changes are amazing, yet the core, the heart of the city remains the same.

Calle Miguelete at Plaza de la Virgen, both Jose’s 1957 and Luna’s 2010 reality

8) Are there any storyline pieces you are worried about? Does reaction to the book worry you?

Does it worry me? Only all the time. Writing a book is like walking around naked, you are fully exposed to embarrassment and ridicule. I feel like a running joke – an author with an anxiety disorder. I dream about being teased about typos. After writing a chapter, I put on a cynical hat and question its believability. With the Luna Montgomery series, I want things to be as realistic as possible. Fortunately, by following real-life scenarios, the possibility of the storyline being over-the-top is nigh impossible. With the flood, it’s all real, as is the babies stolen by the church. None of that needed to be made up. The 2010 storyline gave me more worries. The medical details were something I was careful with – there’s nothing worse than reading/watching something and a character is sick and makes an instant miracle recovery. Anyone who suffered or nursed someone with a serious illness or injury will see right through it. I had to check the detail very carefully. I fight constantly with Luna and Cayetano, to make sure they are believable and full of flaws. Perfection doesn’t exist and neither of them can appear to have the upper hand over the other. They both make mistakes, they both say stupid things, like any couple. I worried, about halfway through, that Luna was being too needy, and then wasn’t being strong enough. At the end, I did worry if all the feminists out there will be disappointed with her life choices, but to me, she does all she needs to do for all around her. She doesn’t have the luxury of making decisions to suit herself. I also worry if Cayetano comes off as arrogant or selfish at times, but have tried to suitably redeem him. You aren’t supposed to like every character all the time anyway.

9 )Why give Luna two children? What’s the point?

There is plenty of point. From the very beginning, I imagined Luna with two sons. Luna is the very first character I ever created, back in 2009 when I was still finding my feet. (You can’t accuse me of not taking my time with the characters. I took 18 months off these characters to work on Canna Medici while I got this series together.) Luna meets Cayetano and their lives are a mess. They meet to uncover murdered relatives, so it’s not a love story. From the very beginning, Cayetano always had María, his wife. That in itself is a nightmare, but to have Luna as a single woman would be too easy, and make her too perfect. I made her a parent because it suits her, she’s the type to cope well with sons. I had to also make her a widow, because that was the only way to make her solo mother, no other scenario worked on Luna and Fabrizio as a couple. I’ve been the child of a solo mother, and know just how amazing they are. To have a male and female lead character makes it easy for them to fall into a relationship, or at least an affair, and by making Luna a widowed solo mother, and Cayetano already married, it gave me far more scope to develop the characters and their interactions. They come from totally different perspectives, and not just because their families sit on opposite sides of the political and religious divide. They cannot understand each other’s situations because they are so bogged down in their own realities. Just when the path seems smooth for a quiet life, I have something to throw in the mix. This isn’t a romance novel (but if you like romance, I have one in the pipeline to come out after my next civil war book, so bear with me!)

10 ) Which of the two books (Blood in the Valencian Soil and Vengeance in the Valencian Water) have you enjoyed writing the most….and why?

That is a really hard choice. BITVS was my baby, I nursed her for quite some before I got the book I wanted. It is centred in the civil war, something that gives me enough inspiration to write 100 books. It is set around a murdered grandfather, something very close to home for me. The issue of relative killed in the civil war and hidden away also hits close to home for me. The story of a kiwi nurse in Spain is something I took the time to understand, follow and genuinely care about. It was great to meet the family of Renee Shadbolt, the real Scarlett Montgomery, and how proud they were of her. Real people in real scenarios flourishing and despairing was what I wanted to create. I will always love BITVS.

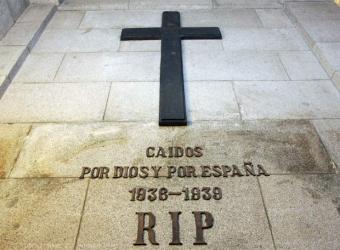

one place – three periods in the series

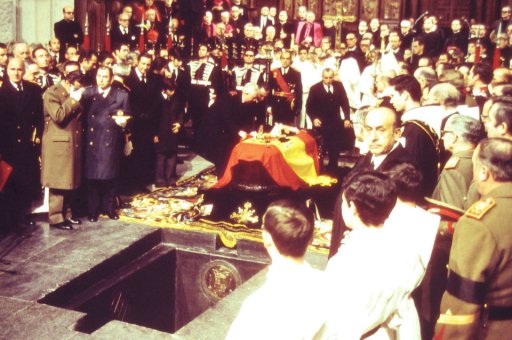

VITVW is totally different. Writing one book and making it my baby seems easy compared to following it up with a suitable sequel. I wanted to continue the series, but at the same time, make a story that can stand on its own. It needed to pack all the punch of the first book, without going over old detail. I can’t remember when I decided to write a Valencia flood novel, but I don’t think it’s been done before (feel free to correct me). It would have been easy to have Luna and Cayetano go back through another civil war story and it probably would have worked, too. But going back to the 1950’s instead of the 1930’s gave the series new life. The third book goes to the 1970’s, so the state of Spain under Franco through the years can be seen in long form. From war in the 30’s, to the heavy-handed rule of the 50’s, to the unstable 70’s, the story of the Beltrán and Morales families can tell a huge story. The present day storyline also gives that chance. BITVS is set in 2009, VITVW in 2010 and then Death in the Valencian Dust in 2013, and Spain changes in this tiny time frame, giving me plenty to work with. As long as Rajoy is in power, enough things will be screwed up, providing plenty of ideas.

I would have to say BITVS is my favourite to write because it was the first in this big project, but VITVW gave me huge satisfaction too, as I feel I have done a really good job with it. I wouldn’t change a thing, and feel my writing style is much better now.

Click here to read the Part 1 with the free book offer Q+A. Part 3 will have all remaining questions, Part 4 is Valencia in photos, and Part 5 is the first chapter, available January 24, the same day as the book release.