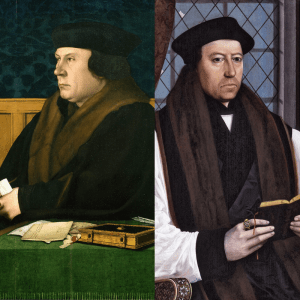

The day after Cranmer’s emotional letter to the King, Cromwell could write to the King directly, something his enemies must have dreaded. Anyone would have known that five minutes before the King would have secured Cromwell’s release. They could not take the risk of Cromwell speaking for himself or to Henry, so when the letter went to the King, nerves in and around the privy chamber would have been on edge. Here, Cromwell gained the chance to defend himself against the bizarre claims of treason and heresy, against the claim he mentioned impotency to Wriothesley, and that he had been anything but the finest servant a monarch. This was Cromwell’s one shot, and he did not waste the opportunity.

CROMWELL TO HENRY VIII, 12 June 1540 (MSS Titus B. I, 273)

Most gracious King and most merciful sovereign, your most humble most obedient and most bounden subject and most lamentable servant and prisoner, prostrates at the feet of your most excellent majesty. I have heard your pleasure by the mouth of your Comptroller which was that I should write to your most excellent highness, such things as I thought mete to be written concerning my most miserable state and condition, for the which your most abundant goodness, benignity and license the immortal God there and on reward, Your Majesty. And now, most gracious Prince, to the matter. First whereas I have been accused to your Majesty of treason, to that I say I never in all my life thought willingly to do that thing that might or should displease your Majesty and much less to do or say that thing which of itself is so high and abominable offence, as God knows who I doubt not shall reveal the truth to your Highness. My accusers your Grace knows God forgive them. For as I ever have had love to your honour, person life, prosperity, health, wealth, joy, and comfort, and also your most dear and most entirely beloved son, the Prince his Grace, and your proceeding. God so help me in this my adversity and confound me if ever I thought the contrary. What labours, pains, and travails I have taken according to my most bounden duty, God also knows, for if it were in my power as it is God’s to make your Majesty to live ever young and prosperous, God knows I would, if it had been or were in my power to make you so rich, as you might enrich all men. God help me, as I would do it if it had been, or were, in my power to make your Majesty so puissant as all the world should be compelled to obey you. Christ, he knows I would for so am I of all other most bound for your Majesty who has been the most bountiful prince to me that ever was king to his subject. You are more like a dear father, your Majesty, not offended then a master. Such has been your most grave and godly counsels towards me at sundry times in that I have offended I ask your mercy. Should I now, for such exceeding goodness, benignity, liberality, and bounty be your traitor, nay then the greatest pains were too little for me. Should any faction or any affection to any point make me a traitor to your Majesty then all the devils in hell confound me and the vengeance of God light upon me if I should once have thought it. Most gracious sovereign lord, to my remembrance I never spoke with the Chancellor of the Augmentations[1] and Throckmorton[2] together at one time. But if I did, I am sure I spoke never of any such matter and your Grace knows what manner of man Throgmorton has ever been towards your Grace and your preceding. And what Master Chancellor[3] has been towards me, God and he best knows I will never accuse him. What I have been towards him, your Majesty, right well knows I would to Christ I had obeyed your often most gracious, grave counsels and advertisements, then it had not been with me as now it is. Yet our lord, if it be his will, can do with me as he did with Susan[4] who was falsely accused, unto the which God I have only committed my soul, my body, and goods at your Majesty’s pleasure, in whose mercy and piety I do holy repose me for other hope then in God and your Majesty I have not. Sir, as to your Commonwealth, I have after my wit, power and knowledge travailed therein having had no respect to persons (your Majesty only except) and my duty to the same but that I have done any injustice or wrong willfully, I trust God shall bear my witness and the world not able justly to accuse me, and yet I have not done my duty in all things as I was bound wherefore I ask mercy. If I have heard of any combinations, conventicles or such as were offenders of your laws, I have though not as I should have done for the most part revealed them and also caused them to be punished not of malice as God shall judge me. Nevertheless, Sir, I have meddled in so many matters under your Highness that I am not able to answer them all, but one thing I am well assured of that, wittingly and willingly. I have not had will to offend your Highness, but hard as it is for me or any other meddling as I have done to live under your Grace and your laws, but we must daily offend and where I have offended, I most humbly ask mercy and pardon at your gracious will and pleasure. Amongst other things, most gracious sovereign, Master Comptroller showed me that your Grace showed him that within these 14 days you committed a matter of great secret,[5] which I did reveal contrary to your expectation. Sir, I do remember well the matter which I never revealed to any creature, but this I did, Sir, after your grace had opened the matter first to me in your chamber and declared your lamentable fate declaring the thing which your Highness misliked in the Queen, at which time I showed your Grace that she often desired to speak with me but I dared not and you said why should I not, alleging that I might do much good in going to her and to be playing with her in declaring my mind. I thereupon, lacking opportunity, not being a little grieved spoke privily with her Lord Chamberlain,[6] for the which I ask your Grace mercy, desiring him not naming your Grace to him to find some means that the Queen might be induced to order your Grace pleasantly in her behaviour towards your thinking, thereby for to have had some faults amended, to your Majesty’s comfort. And after that, by general word of the said Lord Chamberlain and others of the Queen’s Council, being with me in my chamber at Westminster for license for the departure of the strange maidens. I then required them to counsel their masters to use all pleasantness to your Highness, the which things undoubtedly warn both spoken before your Majesty committed the secret matter unto me only of purpose that she might have been induced to such pleasant and honourable fashions as might have been to your Grace’s comfort which above all things as God knows I did most court and desire, but that I opened my mouth to any creature after your Majesty committed the secret thereof to me, other than only to my Lord Admiral, which I did by your Grace’s commandment which was upon Sunday last in the morning, whom I then found as willing and glad to ask remedy for your comfort and consolation, and saw by him that he did as much lament your Highness’ fate as ever did a man, and was wonderfully grieved to see your Highness so troubled, wishing greatly your comfort. For the attaining whereof, he said for your honour saved, he would spend the best blood in his body, and if I would not do the like and willingly die for your comfort I would I were in hell, and I would I should receive a thousand deaths. Sir, this is all that I have done in that matter and if I have offended your Majesty, therein prostrate at your Majesty’s feet. I most lowly ask mercy and pardon of your Highness. Sir, there was also laid unto my charge at my examination that I had retained, contrary to your laws, Sir. What exposition may be made upon retainers I know not, but this will I say, if ever I retained any man but such only as were my household servants but against my will God confound me, but, most gracious sovereign, I have been so called on and sought by them that said they were my friend that constrained thereunto. I received their children and friends, not as retainers, for their fathers and parents did promise me to friend them and so took I them not as retainers to my great charge and for none evil as God best knows interpret to the contrary who will most humbly beseeching your Majesty of pardon if I have offended therein. Sir, I do acknowledge myself to have been a most miserable and wretched sinner and that I have not towards God and your Highness behaved myself as I ought and should have done. For the which, my offence to God while I live I shall continually call for his mercy and for my offences to your Grace which God knows were never malicious nor willful, and that I never thought treason to your Highness your realm or posterity. So God, help me in word or deed, nevertheless I prostrate at your Majesty’s feet in what thing soever I have offended I appeal to your Highness for mercy, grace and pardon in such ways as shall be your pleasure beseeching the almighty maker and redeemer of this world to send your Majesty continual and long health, wealth and prosperity with Nestor’s[7] years to reign, and your most dear son, the prince’s grace, to prosper reign and continue long after you, and they that would contrary, a short life, shame, and confusion. Written with the quaking hand and most sorrowful heart of your most sorrowful subject and most humble servant and prisoner, this Saturday at your Tower of London.

THOMAS CRUMWELL

[1] Sir Richard Rich

[2] Michael Throckmorton, servant to Reginald Pole

[3] Thomas Audley, Baron Walden

[4] The Book of Daniel – Susanna falsely accused by lecherous voyeurs

[5] impotence

[6] Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

[7] Nestor from the Iliad, known for wisdom and generosity, which increased as he aged