El Caudillo. The Generalissimo. Supreme patriotic military hero by the Grace of God. Whatever you want to call him, Franco was a short man with a penchant for moustaches and murder. When people think of dictators, they think of Franco’s mate Hitler, or more current dictators such as Mugabe or the North Koreans with bad haircuts. Some would say Franco was a coward in comparison, or more moderate. If you turn from the word dictator and instead to fascism, the dictionary will give you Franco as a definition. Call Franco whatever you like, but November 20 is the day to celebrate his slow and painful death. The day in 1975 when cava and champagne bottles were popping faster than overheated popcorn. That day, Spaniards, at home and in exile, could finally shake off their not-so wonderful leader.

Born in December 1892 in Galicia, Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde was one in a long line of relatives in the navy. But instead Franco chose the army in 1907, and worked his way through the ranks through wars in Morocco, and was shot in the stomach in 1916, and lost a testicle (it is rumoured). He continued fighting and winning medals, and by the mid-twenties, he was ranked high enough to be before the King in Madrid. The royal family got run out of the country when the Second Spanish Republic took hold in 1931, but it wasn’t until Franco’s cozy position at the army academy in Zaragoza being extinguished did Franco start getting angry. Posted to the Balearic Islands for a few years, Franco got a taste of killing his own people during the miner’s strike in Asturias in 1934. He crushed innocents defending their rights, and the left and right side of politics only continued to divide as bitterness set into the young Republic. After the 1936 elections, all went to hell, and Franco found himself leading an army from Morocco into Spain to depose the Republican government.

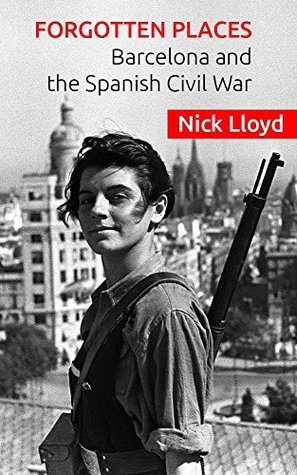

Fast forward through three years of brutal civil war though 1936-1939 (if I explain that in detail, we will be here forever), and Franco’s Nationalist army, backed by fascists, Carlists, monarchists, any right-wing nutball group really, had defeated the Republicans, with the communists, anarchists and general plucky young men and women from Spain and overseas fighting for freedom. After gross atrocities, upwards of 200,000 people were killed. Franco was the leader of Spain, a nation decimated by force and hate. The short, moustached, one-testicled Hitler lover was in control.

Spain was no picnic. So many fled the country, many to France, Mexico, Cuba, Argentina… basically anywhere but Spain. Artists, teachers, bright minds, and those of the left-wing all ran for their lives. Spain skipped the Second World War after basically being in pieces, claiming neutrality, though Franco loved Hitler’s style of hating. While Franco was claiming that Spain had struck gold and all would be well, 200,000 people starved to death in the first half of the 1940’s. The whole decade was spent rounding up people who had supported the Republican side of the civil war, and up to 50,000 were killed, or put in concentration camps, or just ‘disappeared’.

Franco was brutal and bizarre. He could be easily played with wild schemes. But his own plan, being anti-Communist, won him love from the United States. They were allowed to set up military bases, Spain got money and their love for Hitler, Mussolini, etc was swept under the carpet. Spain and its technocrats were keen to move on and make Spain wealthy and prosperous again, though naturally, all spoils only went to the people at the top of the food chain. Spain’s Años de Desarrollo, years of development began through 1961-1973, with Franco promoting tourism, bullfighting, flamenco, everything super-Spanish. Financially, things got much better, but since everyone was doing so poorly, ‘much better’ still wasn’t great. Many Spaniards were still living overseas. Riots broke out at universities, women were still horribly oppressed, with divorce, abortions and birth control illegal. They couldn’t have bank accounts without male oversight, and couldn’t even leave a violent husband, real middle-ages style of living. The church was sticking its evil nose into everything, being gay was illegal, local languages were banned, and nuns loved hitting kids in schools and orphanages.

By 1969, Franco was getting old and handing more power to the lecherous bastards who profited from his reign. It was time to choose an heir. Franco had one daughter (though that has been questioned, given the testicle incident, but never mind), and Franco chose Juan Carlos de Bourbon, grandson to the Spanish King exiled to France in 1931. The young man, dutifully married to a Greek princess, would be modelled and educated in the ways of Francoism – basically being a murderous douche.

Even as Franco was getting super old in the 1970’s, he was still being real bastard, handing down executions just months before his death. Young people were rising up, wanting change in their country, and groups such as ETA wanted their regions’ independence back, as did Catalonia, Galicia, Valencia – basically everyone. In the final months of Franco’s reign, countries were having protests against his execution decisions, Mexico tried to have Spain kicked from the UN, and the Pope wasn’t interested in him anymore, which isn’t cool for a Catholic nation. But on October 1st, Franco have a hate speech from his palace and left in tears. From that moment, his number was up.

Pneumonia, heart attacks and then internal bleeding took hold. Machines kept the old man alive and drugged. Doctors worked day and night for the man who let people be shot by firing squads or starve to death. But after 35 days of pumping life into a frail old man, on November 20, 1975, Franco finally passed away.

The parties started, in Spain and all around the world, where Spaniards had waited for the day. Half a million people went to see his body, just to see the proof for themselves (this figure remains disputed, like all figures during Spain’s 20th century). Spain, which had been lying dormant, could live again. The protege, Juan Carlos, was crowned King, and tossed Francoism aside, opting for democracy. None of that was an easy ride as the road to the Transition began.

The trouble is, those killed during and after the war are still buried in their makeshift graves. Those lecherous wannabes who circled Franco did not lose their place in politics, and among the wealthy and elite. Those who were evil were all given amnesty, to smooth the road for democracy. Justice was never served; Spain’s hard questions remained unanswered for so many. Those who did wrong have grown old, as those who were harmed. The varying levels of independence of Spain’s 17 regions still causes headaches. Does Spain still need to ask questions of its past, or is the future hard enough?

Either way, pop a cork off champagne today, at least to celebrate the freedom Spaniards would have felt on 20 November, 1975.

Read more of what has changed in Spain since Franco’s death, and what is to come – Spaniards aim for a new democracy and end to Franco’s long shadow

Read more about Valle de los Caídos, Franco’s super creepy tomb, where monks will be praying for him today (yes, that’s a thing!)

Read more about Franco’s war, reign, and death in the Secrets of Spain novel trilogy

Comments on this article are now closed.