Valencia, Spain: October 1957 – After a long hot summer, Guardia Civil officers José Morales Ruiz and Fermín Belasco Ibarra have had enough of their lives. Sick of dealing with lowlifes and those left powerless under Franco’s ruthless dictatorship, the friends devise a complex system of stealing babies, to be sent away to paying families. But as the October rains fall, the dry Valencian streets fill with muddy water, and only greed and self-preservation will survive…

It’s 2010, and Luna Montgomery is busier than ever. With the mystery of her murdered grandfather solved, she reluctantly prepares to be the bride in Spain’s ‘wedding of the year’. But four more bodies lie hidden at Escondrijo, Luna’s farm in the Valencian mountains. Her fiancé, bullfighter Cayetano Beltrán Morales, is not eager to have his name brought up in a post-civil war burial excavation. When Cayetano’s grandfather José, an evil Franco supporter, starts to push his ideals on Luna, her decision to join the Beltrán family comes under scrutiny.

The Tour de France is fast approaching, and Luna’s position as a bike mechanic on Valencia’s new cycling team begins to come under pressure. When an ‘accident’ occurs at Escondrijo, lives hang in the balance as more of Spain’s ghosts come to life and tell the story of a flood in 1957…

It’s that time again. With time ticking away until Vengeance in the Valencian Water is released on January 24, it’s time I got onto answering some of your questions! I have merged some questions together, to answer as many as possible, but will post in a few parts. Let’s jump right in.

1 ) What is Vengeance in the Valencian Water all about?

VITVW is the second in the Luna Montgomery ‘Secrets of Spain’ series, which continues right where Blood in the Valencian Soil left off. VITVW follows the same vein – two different time periods, with their own themes that are bound together by similar circumstances. VITVW is centred in Valencia 1957, with a Guardia Civil officer, José Morales and his battle against the struggles of Franco Spain. Common in this time period was the horrendous baby-stealing practices in hospitals, where the church would steal babies from mothers at birth and sell them, with the law on their side. José gets caught up in this vicious circle, only to find his real adversary is the Valencia flood of October 14 the same year. The story runs alongside the 2010 storyline of Cayetano Beltrán, José’s grandson, and his life with Luna Montgomery, which is under pressure. With the financial crisis weighing down Cayetano’s career as a bullfighter and the impending bankruptcy of his grandfather’s huge business, life is increasingly difficult. Luna is still struggling after the recession claimed her job in the first novel, and just as she finds some stability, her late husband’s alleged drug cheating as a professional cyclist rears its head. The long-awaited trial of a Spanish doctor caught doping Tour de France riders leaves Luna to face a legacy she never wanted to be part of. Luna continues pushing to dig up unidentified Spanish civil war bodies, the common clash in Luna and Cayetano’s relationship in BITVS. All the themes in both 1957 and 2010 interlink as ‘coincidence versus fate’ is again explored.

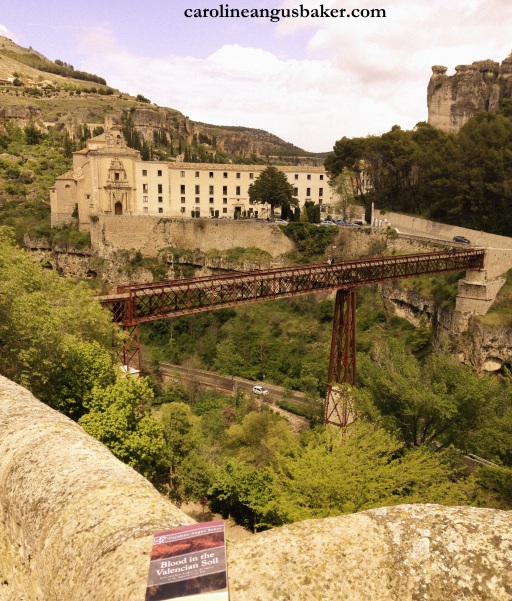

Pretending to be researching in Segovia

2 ) How long did it take to write Vengeance in the Valencian Water?

I started writing in February ’13, with the intention of having the bulk of the storyline completed before my research trip in May. That failed dismally but while in Spain, I learned so many things. Once back from Spain I was busy with Violent Daylight‘s August release and the story went on hold. I didn’t get back to VITVW until October and finished at the end of November. The book dragged out longer than ever planned, and many ‘real-life’ things got in the way. I had the background for the book, with the research on the Valencian flood, the baby black market and the drugs in cycling done a year in advance, so when it came time to flesh out the book, there was no delay. Going to Spain to learn more about bullfighting and the reality of the recession in Spain really helped with the final touches. Because this book had swirled in my mind for so long, the writing was the final piece of the puzzle, rather than just writing and seeing where the book led, as I have done in the past.

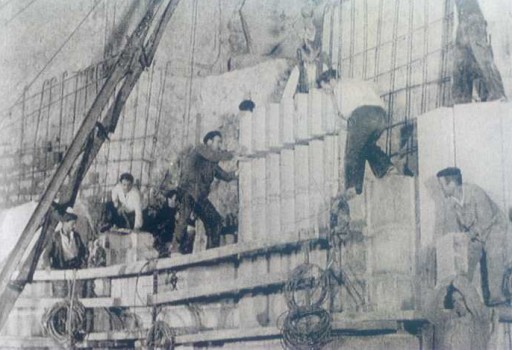

wonderful photo by @v_puerto

3 ) How can you justify being a fan of bullfighting? Bullfighting is grotesque, so why do you condone animal cruelty?

I have heard it all. I have three things that attract internet trolls – bullfighting, supporting cycling (in NZ) and being a feminist. Bullfighting tends to bring out the animal in people themselves. I have been told I am vile, I am cruel, I don’t deserve to be a parent, I am disgusting, my family deserves to be hurt… the list goes on. Are all these people interesting in the way their meat was raised and processed? Bulls raised on ganaderías and sent to bull fights are treated like kings. Quality healthcare, exercise regimes, carefully controlled diets… none of those things are taken into consideration for the chicken or pork in your fridge. Yes, bulls are taunted and exhausted in the ring, surrounded by the real beast of bullfighting – the crowd – who hungers for the animal to die. Is that degrading? Yes – that is without question. Do I feel sorry for the bulls while they stand disoriented and weakened as they get stabbed to death? Absolutely! The combination of watching the animal die, combined with sitting beside people who love to watch the event is not a nice feeling at all. Am I trying to promote bullfighting? I’m not sure if that is even possible – people can make up their minds about the corrida long before they get there. Many argue on the side of tradition, and I can identify with that. Bullfighting is more than killing an animal. The toreros are fascinating men and their dance with death is something I could write about forever. They are brave, proud and skilled. They have a talent that is frowned upon in the modern age, and stand in the ring to cheat death of its right to claim them, and are both reviled and revered every time they do so. (Numbers of men wanting to be toreros is up, not down as expected). I have great respect for these men, but I have no desire to promote cruelty to animals. I don’t plan on opening minds to both sides of the argument – many minds cannot be opened. The bull is the orchestra, the torero is the conductor. The crowd chants for a kill. I don’t write to glamourise the event – in fact, if you read, you’ll find the books regularly grapple with the subject, and show there is more to a torero than his sword.

4 ) Do you need to read Blood in the Valencian Soil before you read Vengeance in the Valencian Water?

A tricky one. Yes and no. Book one tells the story of a lonely bullfighter and a grieving bike mechanic teaming up to unearth a civil war grave, running parallel to the 1939 storyline of their grandparents trying to flee Valencia at the end of the civil war. The story tells of how Luna and Cayetano meet and how unorthodox they are as a team. However, book two tells the story of them battling through the trials of 2010 Spain, alongside unearthing an all-new grave. The story does stand alone, and the book should give you enough of background that you don’t feel like you’ve been denied any detail. But they are designed to run together, with VITVW starting off just a month after BITVS ended.

5 ) Why have alternate storylines? Isn’t that complicated?

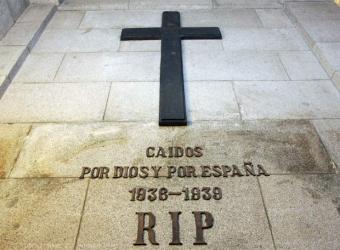

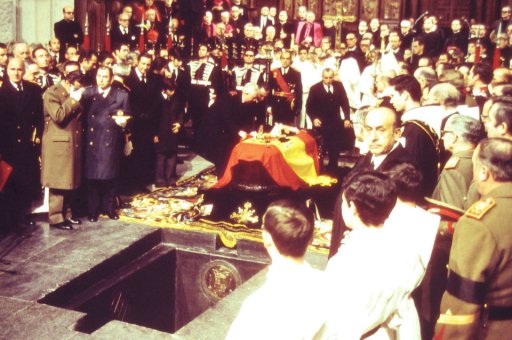

I’ve never had anyone tell me that alternate storylines is complicated. I personally feel that VITVW is even easier to follow than BITVS with the different time periods. The series tells the story of Spanish families throughout the civil war and Franco time period. BITVS is a snapshot of life in 1939, VITVW tells of 1957 Valencian life, and the third book (out 2015) tells the story of 1976 Spain, as the country comes to terms with Franco’s recent death. These times are pitted alongside modern Spain and the very real struggles that the nation is facing. Given the laws that the current Spanish government passes, there is no need to imagine fantastical fiction; reality continues to inspire in depressing ways.

Portal de la Valldigna ’57/’13 – Different and yet the same (photo courtesy of Juan Antonio Soler Aces)

I will be back with part two of the book Q+A in a few days, so if your question hasn’t been answered, have no fear! In the meantime –

For 48 hours only – Blood in the Valencian Soil is free on Kindle/Kindle App. Catch up for free before Vengeance in the Valencian Water is released!

(promotion runs from midnight January 9 until midnight January 11 PST)