Anne Boleyn’s unconventional beauty inspired poets ‒ and she so entranced Henry VIII with her wit, allure and style that he was prepared to set aside his wife of over twenty years and risk his immortal soul. Her sister had already been the king’s mistress, but the other Boleyn girl followed a different path. For years the lovers waited; did they really remain chaste? Did Anne love Henry, or was she a calculating femme fatale?

Eventually replacing the long-suffering Catherine of Aragon, Anne enjoyed a magnificent coronation and gave birth to the future Queen Elizabeth, but her triumph was short-lived. Why did she go from beloved consort to adulteress and traitor within a matter of weeks? What role did Thomas Cromwell and Jane Seymour of Wolf Hall play in Anne’s demise? Was her fall one of the biggest sex scandals of her era, or the result of a political coup?

With her usual eye for the telling detail, Amy Licence explores the nuances of this explosive and ultimately deadly relationship to answer an often neglected question: what choice did Anne really have? When she writes to Henry during their protracted courtship, is she addressing a suitor, or her divinely ordained king? This book follows Anne from cradle to grave and beyond. Anne is vividly brought to life amid the colour, drama and unforgiving politics of the Tudor court.

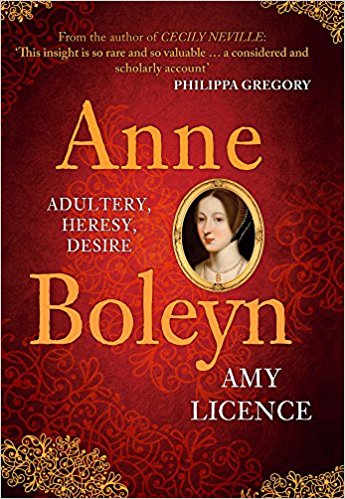

cover and blurb via amazon

~~~

Are you thinking, oh God, another biography of Anne Boleyn? Is there anything else to know? I can tell you that, yes, there is more to know and you should be thrilled to get this one. Amy Licence has practically handed a perfect account of Anne’s life to readers on a silver plate. Come bask in its glory.

Regardless whether you think Anne stole the throne, was a home-wrecking schemer, or she was the king’s love, this book covers all angles, all details and all possibilities. Licence starts with Anne’s family and background, to see how a woman could be so loathed for her background compared to more noble beginnings, despite the fact Anne had a wonderful education abroad, enough for any noble man. The time period of Anne’s life was one where, as a young girl, the royal family of England was relatively stable; Henry married to Katherine, the odd mistress thrown in for good times (his at least). But when Katherine hit menopause and religious opinion was suddenly flexible, Anne’s life could never be the same.

The realities of the time are not romanticised by the author – being a woman was not all gowns and chilling with your lady friends. These people, with their lives dictated by custom, ceremony and family loyalties, were still real people. They loved, they loathed, they hurt like anyone else. The Boleyn family, while not as noble as others (only Anne’s mother was noble born), had their own plans in this world.

Anne served the archduchess of Austria, and Henry’s sister Mary when she was Queen of France. She also then served mighty Katherine, Queen of England. Anne was no fool, no commoner, yet not quite ever noble enough. Her family wanted better, and could you blame them? But the portrayal as the Boleyns as scheming, as pushing daughters forward as whores under the king’s nose has done Anne no favours, and this book can make Anne lovers feel safe she is not portrayed as some witch.

Women routinely became mistresses, as the social order gave this is an avenue, yet was frowned upon (um, who was sleeping with these girls, gentlemen?), and a route Anne’s sister Mary took with Henry, and we shall never know for sure if Mary really wanted the job. But Anne knew, regardless, that she would not do the same thing. She loved Henry Percy, and wanted to have a real marriage, real love, only to have it dashed away thanks to that same social order.

The book delves into Anne’s rise to power as Henry’s paramour, and discusses whether she played him as part of a strategy or whether she was forced into a ridiculous game with no option but to play along. No woman can say so no to a King; Anne had to be his love, his mistress-without-benefits (or did they share a bed? The book discusses), and Henry’s selfish nature sent him down a path Anne couldn’t have imagined. She wanted to be a man’s wife, not whore. Henry, in turn, got Thomas Cromwell to destroy the social order and religious boundaries. Even the most scheming woman couldn’t have predicted that.

Licence uses excellent sources for her biography, and as a person hungry for minor details on certain periods of Anne’s life, I fell upon these pages with great excitement. Anne was smart, she had morals, she had a temper and a strong will, so much so that king chased her long enough to create divorce from the Catholic Church and make her a queen. No one does that for any mistress.

Anne married Henry, and received a coronation with the crown only meant for ordained kings, and gave Henry the Princess Elizabeth. Anne should have had full control of her life by then, only to find she was more helpless than ever. Having given up her virginity but given Henry no son, she fell from favour, and when Henry asked Cromwell to remove Anne to make way for another virgin with a womb, poor Anne was destroyed in a way everyone knows, never learning what a glorious queen her daughter would become. What people didn’t know was the truth over the whole debacle that brought Anne to the executioner’s sword.

As a woman, a spurned one at that, Anne’s history became sullied with lies and cruelty – that she was a femme-fatale who turned into a whore and witch, that she gave birth to a monster child, that she had disfigurements. History was not ready to tell the truth about a smart, powerful woman. Thank God we live in a time where historians like Amy Licence are able to guide readers through Anne’s real history without forcing conclusions on readers.

Edward II is one of the most controversial kings of English history. On numerous occasions he brought England to the brink of civil war.

Edward II is one of the most controversial kings of English history. On numerous occasions he brought England to the brink of civil war.