‘A true Christian confession of the L. Cromwel at his death.’

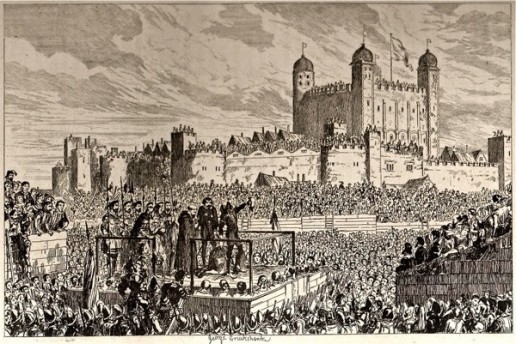

July 28 marked a dramatic day at Tower Hill. The most powerful man in England was to die due to forces entirely outside of his control. Cromwell had selected the perfect queen in Anna of Cleves, a beautiful, well-connected duchess, whose brother Duke Wilhelm of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, and her sister Electress Sybilla of Saxony, had powerful allies and the Schmalkaldic army on their side. But when Duke Wilhelm threatened war with Emperor Charles over the duchy of Guelders while Anna was travelling to England to her marriage, suddenly the duchess who promised powerful allies now also tied King Henry to enter a war he could not win, and would not benefit from at all. Cromwell’s paperwork on the marriage was as strong and watertight as all his work; it could not just be undone, and Henry wed a woman who tied him to war. Henry believed in Cromwell still, even making him an earl in April 1540, but when sexual humiliation reared its head (excuse the pun), Henry snapped and arrested his most faithful servant. Cromwell undid the marriage contract from his room in the Tower, bolstered by fabricated affidavits, talking of Anna being so ugly that Henry couldn’t consummate. An annulment would stop Emperor Charles’ anger at England potentially allying against him, but there needed to be proof, there needed to be someone to blame for the marriage to a duchess who linked England to war. With statements about throwaway comments made to his enemies, Cromwell was attainted for heresy and treason, and conspiring to marry Princess Mary (based on literally no evidence). Even though Henry started to realise his mistake on 9 July, a man attainted could not have his sentence wiped; it would set a legal precedent. But as much as Cromwell’s enemies wanted him dragged on a hurdle to Tyburn and hanged, drawn and quartered as a traitor, or burned at the stake as a heretic, Henry granted Cromwell’s cry for mercy and ordered a beheading.

While primary sources of the day offer sketchy detail, the works Foxe, Hume, Cox, Galter, Herbert, and Hall all offer insights to the day. It is suggested that Cromwell only learned of his style of execution on the morning from William Laxton and Martin Bowes, two sheriffs at the Tower, who came to him after breakfast, which he had just after dawn on a sunny summer’s day. Hume wrote that one thousand halberdiers were there to flank Cromwell’s short walk from the Tower to the scaffold on the hill, for an unfounded fear that Cromwellians would mount an escape bid. There, Cromwell met Walter Lord Hungerford, who was also destined to die for the crimes of incest, buggery and wife-beating, and had lost his mind by the time of his death. The men knew one another through their work for the king, and Foxe wrote that Cromwell tried to comfort the mad baron:

“There is no cause for you to fear. If you repent and be heartily sorry for what you have done, there is for you mercy enough from the Lord, who for Christ’s sake, will forgive you. Therefore, be not dismayed and though the breakfast which we are going to be sharp, trusting in the mercy of the Lord, we shall have a joyful dinner.”

Final words on the scaffold were not a time to defend oneself, fire anger at your enemies or beg for freedom. Cromwell had to deliver a speech to cement his legacy and save his son Gregory, daughter-in-law Elizabeth and their three sons, as well as Richard and Frances Cromwell and Ralph and Ellen Sadler, their very young children, and Cromwell’s wide extended family. Cromwell, accompanied by Thomas Wyatt on the scaffold for support, gave his final speech.

“I am come hither to die, and not to purge my self, as some think peradventure that I will. For if I should so do, I were a very wretch and a Miser. I am by the Law condemned to die, and thank my Lord God, that hath appointed me this death for mine Offence. For sithence the time that I have had years of discretion, I have lived a sinner, and offended my Lord God, for the which I ask him heartily forgiveness. And it is not unknown to many of you, that I have been a great Traveller in this World, and being but of a base degree, was called to high estate, and sithence the time I came thereunto I have offended my Prince, for the which I ask him heartily forgiveness, and beseech you all to pray to God with me, that he will forgive me. And now I pray you that be here, to bear me record, I die in the Catholic Faith, not doubting in any Article of my Faith, no nor doubting in any Sacrament of the Church. Many have slandered me and reported that I have been a bearer of such as have maintained evil Opinions, which is untrue. But I confess, that like as God by his holy Spirit doth instruct us in the Truth, so the Devil is ready to seduce us, and I have been seduced; but bear me witness that I die in the Catholic Faith of the holy Church; and I heartily desire you to pray for the Kings Grace, that he may long live with you in health and prosperity; and that after him his Son Prince Edward that goodly Imp may long Reign over you. And once again I desire you to pray for me, that so long as life remaineth in this flesh, I waver nothing in my Faith.”

Cromwell then went on to pray:

“O Lord Jesus, which art the only health of all men living, and the everlasting life of them which die in thee; I wretched sinner do submit my self wholly unto thy most blessed will, and being sure that the thing cannot Perish which is committed unto thy mercy, willingly now I leave this frail and wicked flesh, in sure hope that thou wilt in better wise restore it to me again at the last day in the resurrection of the just. I beseech thee most merciful Lord Jesus Christ, that thou wilt by thy grace make strong my Soul against all temptations, and defend me with the Buckler of thy mercy against all the assaults of the Devil. I see and knowledge that there is in my self no hope of Salvation, but all my confidence, hope and trust is in thy most merciful goodness. I have no merits nor good works which I may allege before thee. Of sins and evil works, alas, I see a great heap; but yet through thy mercy I trust to be in the number of them to whom thou wilt not impute their sins; but wilt take and accept me for righteous and just, and to be the inheritor of everlasting life. Thou merciful Lord wert born for my sake, thou didst suffer both hunger and thirst for my sake; thou didst teach, pray, and fast for my sake; all thy holy Actions and Works thou wroughtest for my sake; thou sufferedst most grievous Pains and Torments for my sake; finally, thou gavest thy most precious Body and thy Blood to be shed on the Cross for my sake. Now most merciful Saviour, let all these things profit me, which hast given thy self also for me. Let thy Blood cleanse and wash away the spots and fulness of my sins. Let thy righteousness hide and cover my unrighteousness. Let the merit of thy Passion and blood shedding be satisfaction for my sins. Give me, Lord, thy grace, that the Faith of my salvation in thy Blood waver not in me, but may ever be firm and constant. That the hope of thy mercy and life everlasting never decay in me, that love wax not cold in me. Finally, that the weakness of my flesh be not overcome with the fear of death. Grant me, merciful Saviour, that when death hath shut up the eyes of my Body, yet the eyes of my Soul may still behold and look upon thee, and when death hath taken away the use of my Tongue, yet my heart may cry and say unto thee, Lord into thy hands I commend my Soul, Lord Jesus receive my spirit, Amen.”

Cox wrote that Cromwell then turned to Wyatt and sad “farewell, Wyatt,” and that his friend was deeply upset at this stage, and Cromwell added, “gentle Wyatt, pray for me.” Cromwell removed his gown, gave forgiveness to his executioner and prayed him to take his head with a single blow. Conflicting reports exist of what came next. The news of the execution travelled Europe, changing with every letter. Hume wrote Cromwell’s head came off with a single blow. But Galton wrote that the axeman, a “ragged and butcherly wretch” and that the first blow instead hit Cromwell’s skull, and that it took half and hour to cut through Cromwell’s neck. While that seems like a story built on dramatics and exaggeration, regardless of the number of blows required, Cromwell would have been unconscious or dead within seconds.

Hungerford, however, was quickly killed without fanfare or wise words, and Cromwell’s mangled head went on London Bridge like all the rest, his body buried at St Peter ad Vincula, close to Anne Boleyn, whom the king had ordered killed during an Easter conversation with Cromwell only four years earlier. King Henry married Katheryn Howard at Oatlands the same day, not that any knew that at the time. No one who rose in the English court escaped eventual fates like this; it would be surprising if Cromwell had never considered this as his eventual fate.

Thomas Cromwell was undoubtedly the genius of the English court, a man whose mind far exceeded those about him. While his genius was exploited by King Henry, whose orders Cromwell could not refuse, it meant that many never truly appreciated Cromwell, too busy sneering at the rank of his birth. These people were only in power due to their birth, and should have been grateful to breathe the same air as a man who far exceeded them in intelligence, generosity and charm.

~~~

Cromwell’s final speech: Passages from Foxe’s Ecclesiastical History, Vol. ii. p 433

John Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1563

Arthur Galton, The Character of Times of Thomas Cromwell, 1887

Edward Hall, The Triumphant Reigne of Kyng Henry the VIII, vol 2, p306-7

Edward Herbert, Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth, Bodleian Library Oxford, Folio 624, 462

Richard Cox, Elizabethan Bishop of Ely, Corpus Christi College Cambridge, Parker Society MS 168 f. 209rv

Martin Hume, The Chronicle of King Henry VIII 1889, p104